Most of us say we want to save more, but the month somehow disappears before the money does. That’s where a realistic, down‑to‑earth family budget comes in—not as a punishment, but as a steering wheel. When you build a family budget planner for saving money that actually fits your habits, it stops feeling like a diet and starts working more like a GPS: you still choose the route, but you can finally see where you’re going and what the detours cost.

—

Clarifying the basics: what “budget” and “savings” really mean

Before comparing approaches, it helps to be strict with definitions instead of relying on intuition. A budget is a forward‑looking plan for how you will allocate your income across spending, saving and debt payments over a specific period—usually a month. It is not just a list of past expenses; that list is a spending log or transaction history. Savings are the part of income that is deliberately not spent now so it can serve a later goal: an emergency fund, a house down payment, college costs, or early retirement. When we talk about *how to create a family budget and savings plan*, what we really mean is designing a repeatable process that assigns every unit of income a job—today or in the future—so you’re not relying on willpower in the last week of the month.

—

Visualizing the money flows: simple text‑based diagrams

Let’s sketch how money moves through a typical household. Picture a flow diagram in your head:

– Step 1: Income arrives

`Salary + side income + benefits -> Family account`

– Step 2: Money splits into three main channels

`Family account -> [Essentials] + [Non‑essentials] + [Savings & Debt payoff]`

– Step 3: Each channel branches further

`[Essentials] -> rent, groceries, utilities, transport`

`[Non‑essentials] -> dining out, entertainment, impulse buys`

`[Savings & Debt payoff] -> emergency fund, goals, loan payments`

In a healthy, saving‑oriented structure, the diagram looks more like this:

`Income -> Pay yourself first (Savings) -> Essentials -> Non‑essentials`

That single reordering—taking savings off the top instead of saving “whatever is left”—is the core design decision in most effective budgeting worksheets for families to save money. The technical tools differ, but this logical sequence is the backbone.

—

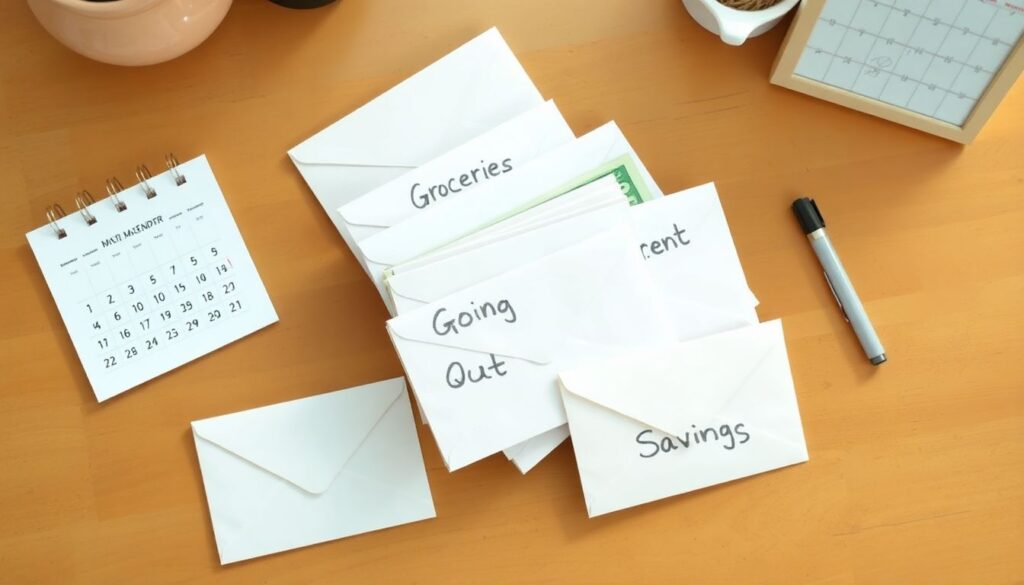

Different budgeting philosophies: envelope, 50/30/20, and zero‑based

There isn’t just one “correct” family budget; there are competing models, each with its own logic. The envelope method is one of the oldest: you split cash into physical envelopes labeled “Groceries,” “Gas,” “Going out,” and so on. When an envelope is empty, that category is done for the month. In digital form, many apps mimic this via “category balances” instead of paper. A second approach, the 50/30/20 rule, is ratio‑based: roughly 50% of net income goes to needs, 30% to wants, 20% to savings and debt repayment. A third, more detailed method is zero‑based budgeting, where every unit of income is assigned to a category until nothing is unassigned—income minus expenses and savings equals zero on paper. Compared with the others, zero‑based budgeting is more precise but requires more tracking effort and discipline.

—

Pros and cons: which approach works for which family?

If your biggest problem is overspending on flexible categories—dining out, groceries that become waste, or impulse online purchases—the envelope style creates hard physical or digital limits. You *see* that the “Restaurant” bucket is almost empty, which makes you pause. On the downside, it can feel restrictive and doesn’t adapt well when your income or bills vary a lot month to month. The 50/30/20 rule, by contrast, is easy to remember and quick to set up, but it can be too coarse: some high‑cost‑of‑living areas simply don’t allow 50% for “needs,” and some families with debt might need more than 20% going to savings plus repayments. Zero‑based budgeting shines for families juggling irregular income, multiple goals, and debt, because it forces you to prioritize each paycheck—but it demands the most time and meticulous attention, a trade‑off not everyone is ready for.

—

Apps, spreadsheets, and pen‑and‑paper: comparing tools

Once you pick a philosophy, the next question is tooling. For some households, a simple shared spreadsheet is still the best budgeting app for families in practice, because both partners understand how it works and it’s easy to customize categories and formulas. Dedicated apps add automation: they import bank transactions, categorize spending, and show progress bars for each goal. That automation saves time but can create a “black box” effect where you trust the app’s numbers without really understanding them. Pen‑and‑paper systems, or a whiteboard calendar on the fridge, give maximum transparency and involvement, but at the cost of manual entry. When assessing tools, the main technical criterion is not feature count but behavioral fit: Will everyone actually open and update it at least once a week?

—

Step‑by‑step: building a realistic family budget that favors saving

Rather than inventing numbers from thin air, start from actual data. Collect one to three months of bank and card statements and categorize every transaction. This forensic step reveals your true baseline: typical grocery spending, recurring subscriptions, transport, and all the “where did that go?” amounts. Then build your first draft budget using that real pattern, not wishful thinking. Next, insert saving as a non‑negotiable line item right after income, not at the end. For instance, you might start with 5–10% into an emergency fund before tackling long‑term investing. The goal is a budget that can survive contact with real life: birthdays, school trips, car repairs. If it only works in a perfectly quiet month, it’s not robust enough.

—

Numbered roadmap: from chaos to a saving‑focused budget

1. Map your income sources

List every predictable inflow: salaries, benefits, child support, side gigs. Use net income (after tax) for clarity.

2. Audit the last few months of spending

Group transactions into logical categories: housing, food at home, eating out, kids, transport, health, fun, miscellaneous, debt payments.

3. Define concrete savings goals

Decide target amounts and timelines: emergency cushion, vacations, car replacement, home down payment, or extra mortgage payments.

4. Choose a budgeting philosophy

Pick between envelope‑style caps, 50/30/20 percentages, or zero‑based precision, based on your temperament and time.

5. Select a tool you’ll actually use

Spreadsheet, notebook, or an app—whichever you’re most likely to open weekly.

6. Allocate income on paper first

Decide how much goes to savings right away, then to fixed bills, then to flexible spending categories until you reach zero leftover.

7. Automate transfers and bill payments

Set automatic moves to savings accounts the day paychecks arrive, and auto‑pay consistent bills where possible.

8. Review weekly and adjust monthly

Hold a 15–20‑minute family “money check‑in” to compare plan vs. reality and tweak amounts before the next month.

—

Comparing DIY budgeting to professional financial help

Managing everything yourself gives maximum control and zero direct cost, which is why most families start with DIY spreadsheets or free apps. However, there are trade‑offs. You may miss tax‑efficient strategies, underfund certain goals, or underestimate risks like disability or job loss. That’s where professionals enter the picture. When you search for family financial planning services near me, you’ll find advisors offering full plans, from budgeting and debt strategies to investing and insurance analysis. They bring structure, scenario modeling, and an external perspective. On the other hand, they charge fees, and quality varies widely. For many households, a sensible compromise is to design and run the day‑to‑day budget internally, and periodically consult an advisor to audit the big picture and stress‑test long‑term assumptions.

—

Short‑term hacks vs. long‑term systems

It’s tempting to hunt for hacks: cancel three subscriptions, eat out less, buy cheaper brands, and assume saving will magically happen. These tweaks matter, but they’re not a system. A true system blends rules, habits, and structure. For example, combining a zero‑based layout with automatic transfers turns saving into the default rather than a monthly debate. Short‑term tactics can be useful experiments—like a “no‑spend weekend” or a challenge to cut grocery waste by 20%—but you anchor them inside a framework that remains stable: regular reviews, clear categories, and predictable contributions to each goal. When you evaluate any new trick, ask: does this integrate into our existing budget architecture, or is it just a one‑off sprint we’ll abandon next month?

—

Making it a team project: involving partners and kids

A technically perfect budget fails if only one adult understands it. Budgeting for a family is a coordination problem, not just a math problem. At minimum, both partners should agree on priorities: how much peace of mind an emergency fund is worth, what trade‑offs they accept for a vacation, or whether paying the mortgage faster beats investing. In practice, this might look like a monthly meeting where you walk through a simple diagram: “Here’s the income box at the top, here’s the savings box, here are the key spending boxes; here’s where we went over or under.” With children, you can mirror the structure at their scale: allowance split into three envelopes—spend, save, give—so they see that money naturally flows into different purposes, not just instant consumption.

—

Choosing and customizing planning tools

When you evaluate any family budget planner for saving money, look beyond pretty dashboards. Check whether it supports multiple accounts, shared access for partners, and separate “buckets” for different goals within savings. Spreadsheets excel at flexibility: you can add custom formulas for irregular expenses like annual insurance or school fees by dividing yearly totals into monthly “sinking funds.” Apps shine at friction reduction: transaction imports mean you focus on decisions, not data entry. Many also include built‑in budgeting worksheets for families to save money, guiding you through common categories and suggesting target percentages. The best choice is the one that fits your tolerance for detail, your tech comfort, and your schedule. You can always start simple and layer complexity only if you feel blind spots, rather than overwhelming yourself on day one.

—

Bringing it together: a budget that naturally encourages saving

When you compare all these approaches—envelope vs. percentage rules vs. zero‑based, DIY vs. professional, analog vs. digital—the most important differences aren’t cosmetic. Systems that genuinely promote saving share three traits: savings are planned *first*, not last; money flows are visible in some kind of diagram or worksheet; and the process is light enough that you keep using it month after month. Whether you rely on a notebook, a spreadsheet, or what you consider the best budgeting app for families, the goal is the same: transform saving from a vague intention into the default outcome of how your family budget is engineered. Once the structure is in place, small course corrections beat heroic efforts, and saving stops feeling like sacrifice and starts feeling like progress.