Why Your Credit Report Matters More Than You Think

Your credit report is basically your financial “medical record”: banks, landlords, and sometimes employers use it to judge how risky it is to deal with you. It summarizes your borrowing history, payment behavior, and current obligations. According to the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), credit reporting is consistently the number‑one source of consumer complaints: from 2021 to 2023, credit reporting issues made up roughly 50–60% of all complaints they received each year. Older research from the Federal Trade Commission found that about 20% of consumers had at least one potentially material error on a report. Even though the FTC numbers are a bit dated, the steady volume of complaints over the last three years shows that incorrect data and confusing layouts are still common problems. That’s why learning how to read a credit report for beginners isn’t just “nice to have” — it’s a core financial survival skill.

Essential Tools Before You Start

Before diving into the contents of your report, you’ll want a few basic tools and accounts ready, so you’re not hunting for logins and documents mid‑way. First, you’ll need access to all three major U.S. credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian and TransUnion. Federal law entitles you to a free credit report check from each bureau at least once a year through the official AnnualCreditReport.com portal; since the pandemic, they’ve periodically expanded this access, so it’s worth checking the current frequency when you log in. Second, create secure online accounts directly with each bureau. This lets you download updated reports, place freezes, and initiate disputes without mailing paper forms. Finally, have a password manager, recent bank and card statements, and your ID documents handy — these help you verify accounts and flag anything that doesn’t belong to you.

Digital Tools and Services That Help

You don’t need fancy software to understand your credit file, but a few digital helpers can simplify the job. Many banks and card issuers now offer built‑in dashboards that show your credit score, key risk factors and even alert you when new accounts appear. There are also standalone credit report monitoring services that track changes across one or more bureaus and send real‑time notifications about new inquiries, late payments being reported, or suspicious address changes. Over the last three years, these monitoring tools have grown more popular as identity theft complaints have risen; the FTC reported millions of fraud and identity theft reports between 2021 and 2023, with credit card fraud consistently near the top. If you prefer a minimalist approach, you can skip paid subscriptions and simply set calendar reminders to pull your free reports on a regular cadence and review them line by line.

Getting Your Actual Credit Reports

The first operational step is acquiring fresh copies of your reports. For most U.S. consumers, the safest starting point is the official AnnualCreditReport.com site, which centralizes access to all three bureaus. From there you can request each file, choosing online viewing or downloadable PDF. To authenticate you, the system will ask questions about past loans, addresses, or payment amounts — answer carefully, because a wrong answer can lock you out and force you into a slower mail‑in or phone verification process. If you’ve been denied credit in the last 60 days, you’re also entitled to an additional free report from the relevant bureau. For maximum clarity, try to pull all three reports within the same week; that way, when you compare them, you’re looking at roughly synchronized data instead of snapshots from different months.

Setting Up a Simple Review Schedule

Once you have the initial reports, think of this as the start of a recurring process, not a one‑time chore. A practical schedule many people use is to review one bureau every four months, rotating through Equifax, Experian and TransUnion. This “staggered” approach keeps you informed almost year‑round without paying for extra access. Since 2021, more consumers have adopted this rotation strategy as they became aware of data breaches and account takeover risks, shown by increasing identity theft complaint trends in FTC and CFPB data. Whether you rotate or pull all three at once each year, the key is consistency: set repeating reminders on your phone or calendar, and attach your downloaded PDFs to a secure folder so you can track changes over time.

How a Credit Report Is Structured

When you open the report, the layout can feel cryptic, but most bureaus follow the same core structure. At the top, you’ll see personal identifying information: name variations, Social Security number (masked), current and past addresses, phone numbers and sometimes employers. Next come your credit accounts (often labeled “trade lines”): credit cards, auto loans, mortgages, student loans and other installment or revolving accounts. Each line shows the creditor name, account number (usually partially masked), type, credit limit or original loan amount, current balance, and a month‑by‑month payment history coded with numbers or letters. Then you’ll see public records and collections, such as bankruptcies or third‑party collection accounts. Finally, the “inquiries” section lists who has accessed your report, separated into hard inquiries (visible to lenders and can affect your score) and soft inquiries (only visible to you). Once you recognize this skeleton, the report becomes far less intimidating.

Key Terms You’ll Keep Running Into

As you read, you’ll encounter specialized jargon that’s worth decoding once so you don’t have to guess. “Revolving account” usually refers to credit cards and lines of credit where the balance can go up and down, while “installment account” refers to fixed‑payment loans like auto or personal loans. “Charge‑off” means a lender has written the debt off as a loss, which is serious from a scoring perspective, even if you later pay it. “Delinquency” indicates late payments, often broken down by 30, 60, 90, or 120+ days past due. You may also see “utilization,” which is the ratio of your balance to your credit limit; higher utilization is correlated with lower scores. Learning this vocabulary once will make every future report easier to parse and will help you interpret what lenders and the best credit repair companies are actually talking about when they assess your situation.

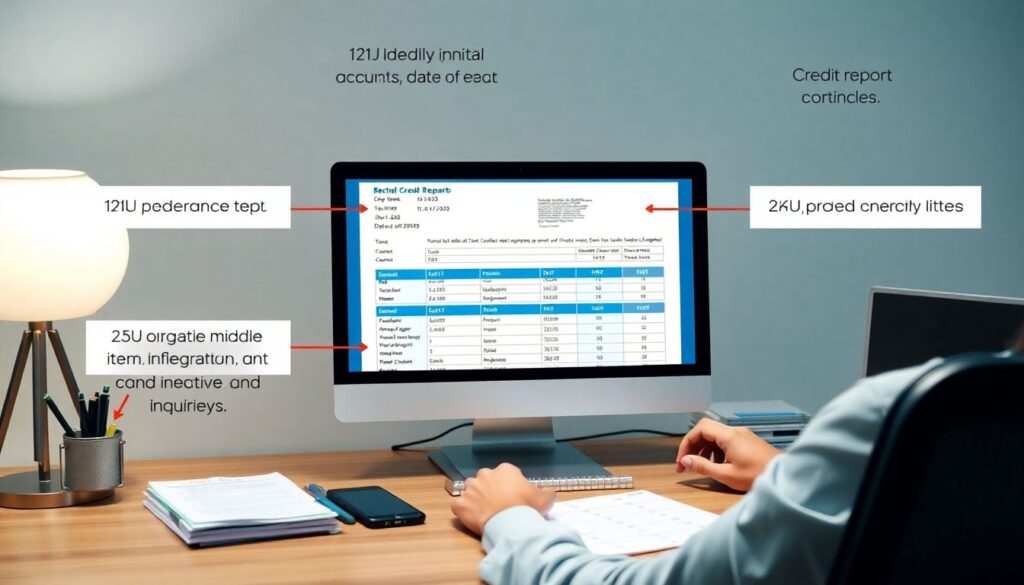

Step‑by‑Step: Reading Your Credit Report Like a Pro

To avoid getting lost in the details, use a systematic, repeatable process each time you open a report. Start with identity data, then move into accounts, then into negative items and inquiries. This reduces the chance of missing subtle issues such as an incorrect middle initial or an address you’ve never used, which can be early indicators of mixed files or identity theft. Over the past few years, regulators have noted that many complaints stem from basic mis‑matching of identities, not just from payment disputes, so don’t skip this “boring” part. After that, scanning account‑by‑account becomes more intuitive, especially if you keep recent statements or your budgeting app open in another window for quick cross‑checks.

- First pass: Verify personal information and addresses.

- Second pass: Match every listed account to your records.

- Third pass: Check payment history and status codes for each trade line.

- Final pass: Review public records, collections and all hard inquiries.

Checking Personal and Address Information

Start at the top, where your personal profile lives. Confirm that your name is spelled correctly, that any listed aliases are legitimately yours, and that your date of birth and partially masked Social Security number look right. Then examine the address list. It’s normal to see several historical addresses if you’ve moved often in the last decade, but you shouldn’t see places you’ve never lived or cities you’ve never visited. Also look at phone numbers and employers; outdated items are fine, but unknown ones are red flags. Many identity theft cases discovered since 2021 began with something as simple as a mystery address or phone number on a credit report, so if you spot those, make a note and plan to investigate further rather than assuming it’s a harmless typo.

Reviewing Accounts and Payment History

Next, go line by line through your open and closed accounts. For each one, confirm that you recognize the lender, the account type and roughly when it was opened. Some lenders appear under unfamiliar legal names, so if something looks odd, cross‑reference your statements or search the name online before concluding it’s fraud. Pay special attention to the payment history grid, which often uses numeric or letter codes; a series of “OK” or “0” entries generally means on‑time payments, while numbers like “30,” “60,” or “90” mark the months where you were late by that many days. Over the last three years, as inflation and higher interest rates squeezed budgets, late‑payment rates on certain types of consumer debt have ticked upward according to industry data, so it’s especially important to know exactly which months show as late and whether that matches your recollection. Misreported late payments are among the most damaging — and most frequently disputed — errors.

Spotting Collections, Public Records and Inquiries

The most intimidating part for many beginners is the negative‑information section. Here, look for collection accounts and any public records that might still be reported. Medical collections, utility bills and old cellphone accounts often show up here and can be surprises if you forgot about a final bill. Then review the list of hard inquiries from the last two years; each one should align with a credit application you remember making. A cluster of inquiries you don’t recognize could signal attempted fraud, especially if they’re tied to banks or auto lenders you’ve never contacted. Recent years have seen persistent identity‑theft activity, so treat unexplained inquiries seriously. Soft inquiries, like those from your own free credit report check or pre‑approved offers, don’t affect your score and are mostly informational, so there’s no need to worry about those.

Using Statistics to Benchmark Your Situation

Understanding your report is easier when you have some context about how common various issues are. While exact numbers for 2024–2025 are still emerging, data through 2023 paint a clear picture. The CFPB has reported hundreds of thousands of complaints per year about credit reporting alone, with volumes remaining elevated since the COVID‑19 period. Industry studies over the past decade have also suggested that a sizable minority of consumers — often quoted around one in five — have at least one error that could affect their score or access to credit. Meanwhile, surveys since 2021 show more people are checking their credit more often, partly because many lenders now provide scores in their apps for free. If you see a few small discrepancies on your report, you’re not an outlier; the real question is how quickly you spot and correct them, and whether you build a routine that keeps future issues from snowballing into serious denials or higher interest costs.

Fixing Errors and Handling Problems

If you find information that looks wrong, outdated beyond the legal reporting period, or clearly belongs to someone else, you have the right to challenge it. The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) requires bureaus to investigate disputes, usually within 30 days, and to correct or delete inaccurate data. The fastest route for many people is to dispute errors on credit report online, using the dedicated dispute portals offered by each bureau. There you can describe the issue, upload supporting documents such as bank statements or letters, and track the dispute status. Over the last three years, regulators have emphasized the importance of submitting clear, specific dispute letters instead of generic templates; investigations are more likely to succeed when you explain precisely what is wrong, why it’s wrong, and what documents back you up, rather than just saying “this is not mine” with no details.

- Gather evidence: statements, payment confirmations, ID documents.

- File disputes with both the bureau and the original creditor if needed.

- Set reminders to check back within 30–45 days for updates.

- Request written results and a fresh copy of your corrected report.

When to Consider Professional Help

Most people can fix straightforward issues themselves, but complex cases sometimes justify outside assistance. For example, if your identity has been stolen and multiple fraudulent accounts have appeared across several bureaus, or if you’re dealing with older bankruptcies and judgments that are reported inconsistently, you may feel overwhelmed. In those scenarios, some consumers look into the best credit repair companies or consult consumer‑law attorneys who specialize in FCRA cases. If you go this route, research thoroughly: check regulatory actions, read recent reviews, and be wary of firms that promise specific score increases or urge you to dispute accurate negative items. Regulators in recent years have taken enforcement actions against abusive operators in this industry, so a cautious, evidence‑driven approach is critical. In many situations, a nonprofit credit counseling agency or a one‑time legal consultation can be more cost‑effective than a long‑term repair contract.

Ongoing Monitoring and Long‑Term Habits

Understanding a single report is just the starting line; staying on top of changes is where you really protect yourself. Decide whether you prefer a DIY rhythm — rotating your free reports and setting up account alerts with your bank — or whether paid credit report monitoring services make sense for your risk level and comfort. People who’ve recently experienced data breaches, had their wallet stolen, or seen suspicious activity may benefit from more intensive monitoring, while others may be fine with periodic manual checks. Since 2021, a growing share of consumers have adopted mixed strategies: using free tools from card issuers to track scores monthly and combining that with annual full‑report reviews. Whatever you choose, combine it with basic security hygiene: strong unique passwords, multi‑factor authentication with your financial institutions, and quick reaction to any unfamiliar charges. Over time, your credit report becomes less of a mystery file and more of a dashboard you understand and actively manage.

Bringing It All Together

Once you’ve gone through this process a couple of times, your credit report stops feeling like a secret code and starts looking like a structured log of your financial life. You know how the sections fit together, you recognize key terms, and you can tell at a glance whether something looks out of place. You don’t need an advanced finance degree to interpret it — just a methodical approach, some patience and a willingness to dig into details when something doesn’t add up. As you keep pulling reports, updating your own records and resolving occasional issues, you’ll not only guard against errors and fraud, but also make smarter decisions about borrowing, paying down debt and planning big milestones like mortgages or car loans. Treat your report as a living document you review regularly, not a static score you fear, and you’ll be far better positioned to navigate the credit system on your own terms.