Why your paycheck looks smaller than you expect

Your first real paycheck is often a shock: the number you were promised and the money that actually lands in your account look suspiciously unrelated. To make sense of that gap, you need paycheck deductions explained for beginners in plain language, but without skipping the technical details that drive those numbers. Every line on the stub follows rules set by tax law, benefits plans and your employer’s payroll system, so nothing is random, even if it feels that way. Once you see how gross pay turns into net pay through a series of structured subtractions, you can start checking for errors, planning your budget and even steering how much is withheld instead of staying at the mercy of an opaque process you don’t control or understand.

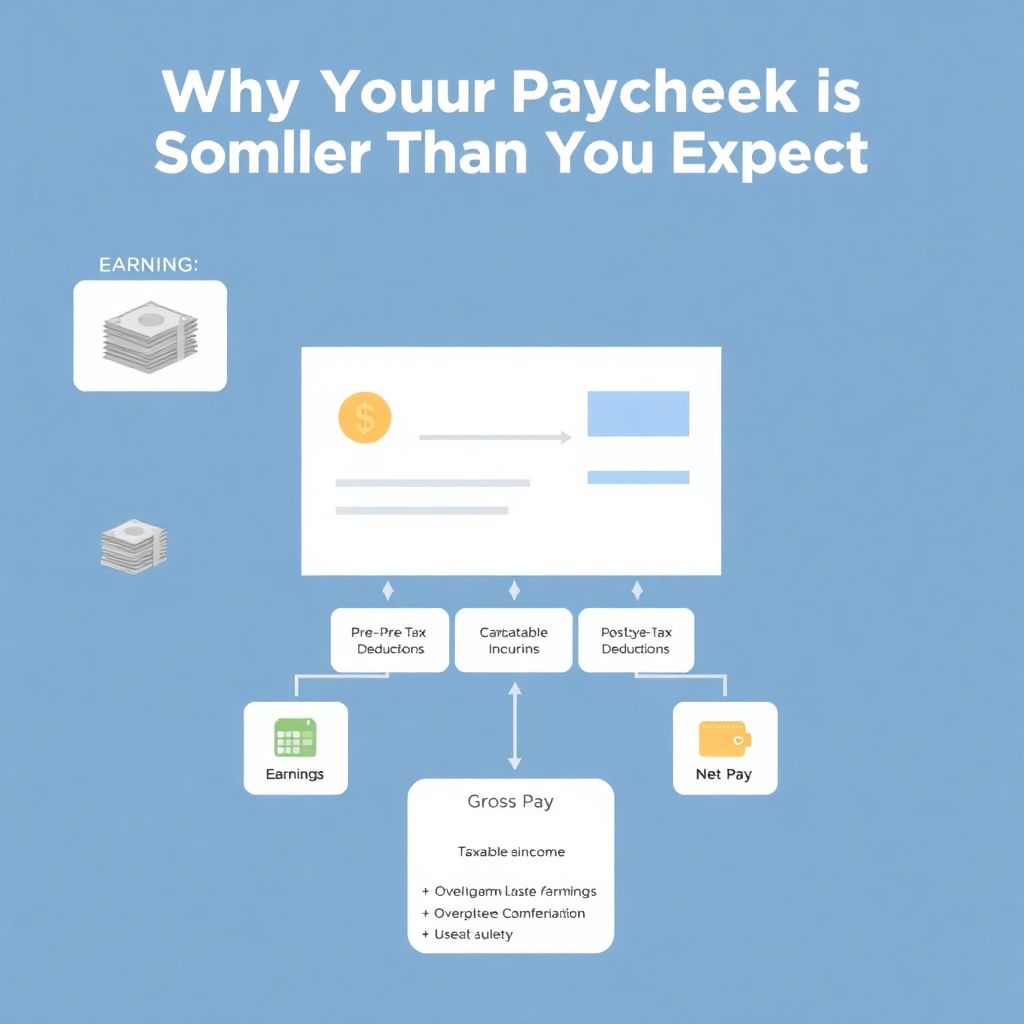

Gross pay vs. net pay: the core equation

At the top of almost every stub you’ll see “gross pay” — the total you earned before anything is taken out — and “net pay,” which is what you actually receive. In between sits the entire deduction pipeline. A simple conceptual model is: [Diagram: Gross pay → pre‑tax deductions → taxable income → taxes → post‑tax deductions → net pay]. Each arrow represents a category of calculations the payroll engine performs every pay period using tax tables, benefit rates and your personal settings. Different countries and states label pieces differently, but the main logic holds: reduce gross pay with certain adjustments, compute taxes on the remaining taxable base, then subtract any after‑tax items such as garnishments or some insurance premiums.

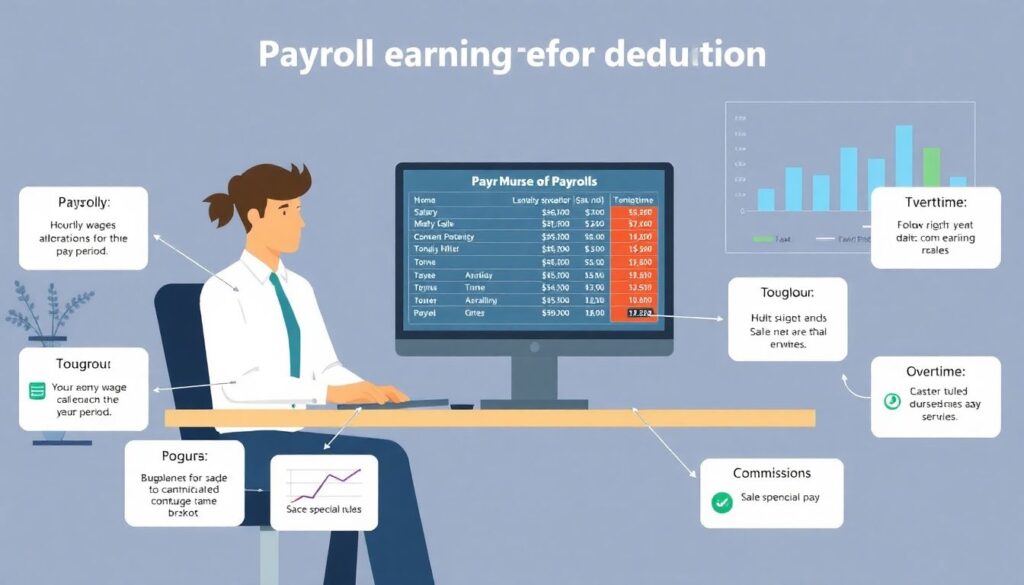

Regular wages, overtime and special pay

Before deductions are even relevant, your employer computes the “earnings” part: hourly wages, salary allocations for the period, overtime multipliers, shift differentials, bonuses and commissions. Each of these may be taxed in the same bracket but sometimes follow special rules, for example supplemental wages like bonuses can be subject to a flat withholding method. [Diagram: Hours × Rate = Base earnings; plus overtime and bonuses = Total earnings]. Understanding which part of your pay is recurring and which is one‑time helps you interpret fluctuations in deductions, because some items, such as percentage‑based 401(k) contributions or Social Security tax, scale directly with total earnings and therefore spike in bonus periods without indicating anything is broken in payroll.

Mandatory paycheck deductions: taxes and social programs

The most unavoidable elements are mandatory deductions, primarily income taxes and social insurance contributions. In the US, those are federal income tax, state and sometimes local tax, plus Social Security and Medicare. [Diagram: Taxable income → apply brackets → sum = income tax withholding]. The payroll engine estimates your annual earnings based on the current paycheck and then uses IRS and state tables to approximate your final liability, converting that into a per‑pay‑period withholding. This is why changing your Form W‑4 or its local equivalent shifts how much is held back. Social insurance lines usually show as flat percentages up to annual caps, so when you hit a cap later in the year, those deductions may suddenly drop, raising your net pay without any raise.

Voluntary deductions: benefits and savings

Voluntary deductions exist because you opted into benefits or savings plans, often via new‑hire onboarding portals. Some are pre‑tax, like many retirement contributions and health premiums, meaning they reduce your taxable income before income tax is computed; others are post‑tax, such as Roth contributions or some supplemental insurance. [Diagram: Gross pay – pre‑tax benefits = lower taxable income → lower tax → higher net]. This ordering is why pre‑tax benefits are so powerful: they cut both your current tax bill and, in many cases, your future tax exposure. The trade‑off is reduced take‑home cash now, so beginners should compare scenarios, for example with and without a 5% 401(k) contribution, to see how a relatively small net reduction today can produce much larger long‑term savings with employer matching and compounding returns over time.

How to read my paycheck stub and deductions step by step

Most stubs follow a logical grouping even if the layout looks cluttered. A practical way to approach how to read my paycheck stub and deductions is top‑down: confirm the pay period dates and hours or salary allocation, then trace earnings totals, followed by tax lines, benefit lines and year‑to‑date aggregates. [Diagram: Section 1 Earnings | Section 2 Taxes | Section 3 Benefits | Section 4 Employer contributions]. Year‑to‑date (YTD) columns are crucial because they let you verify cumulative tax withheld against what online estimators predict for your total annual obligation. If a line item appears only once, such as a correction or retroactive adjustment, cross‑check the description against HR or payroll notifications instead of assuming it’s standard, since one‑off adjustments often explain sudden swings in a single paycheck.

Comparing approaches: manual tracking vs. calculators vs. automation

People learning this system usually gravitate toward three approaches, each with trade‑offs in effort, accuracy and control. A purely manual method means reconstructing the formula chain yourself in a spreadsheet: you enter gross pay, define pre‑tax deductions, apply official tax brackets and add post‑tax items. This yields transparency and teaches the mechanics but demands time and ongoing maintenance as laws change. By contrast, a paycheck calculator after taxes and deductions automates the math using current tax tables; you plug in your pay cycle, location, filing status, benefits and see an instant net estimate. The downside is limited customization and sometimes simplified assumptions, yet for most beginners it’s a fast, low‑friction way to test “what if I change my withholding or 401(k) rate?” without diving into full tax software.

Role of payroll services and employer systems

Inside the company, dedicated platforms handle the complexity of recurring calculations, remittances and reports. Modern payroll services to manage employee paycheck deductions integrate tax rules for multiple jurisdictions, benefit provider feeds and compliance checks, then generate both pay stubs and filings automatically. From your perspective, the key implication is that most arithmetic errors are rare but configuration errors — wrong tax state, mis‑entered marital status, missing benefit elections — are common. Comparing your expectations with the stub and requesting a payroll audit when something looks off is more effective than trying to recalc everything manually. Compared with ad‑hoc spreadsheets or generic calculators, employer systems have authoritative data, but they also enforce defaults that might not align with your optimal tax strategy until you actively update your profile.

Using tax tools to optimize your deductions

Once you grasp the flow, optimization becomes less about guessing and more about modeling. The best tax software to optimize paycheck withholding and deductions usually offers “withholding checkups” that simulate your full‑year tax based on pay stubs and other income sources, then recommend W‑4 adjustments or estimated payments. This software approach goes deeper than standalone calculators by incorporating credits, deductions and side income that payroll systems never see. Compared with trusting default employer withholdings, using such tools reduces the risk of both under‑withholding, which leads to an unexpected bill, and large refunds, which indicate you gave the government an interest‑free loan. The most effective habit is to rerun scenarios after major life changes — marriage, dependents, raises — and update your payroll settings before the next pay cycle hits.

Choosing the right strategy as a beginner

For someone just starting, the most practical route is staged: first, decode one paycheck using the conceptual diagrams above until each line makes sense; second, validate that against a third‑party calculator; third, tweak benefits and withholding with HR tools, then recheck the next stub. [Diagram: Understand → Validate → Adjust → Monitor]. Compared with blindly accepting whatever appears in your banking app, this loop gives you both confidence and leverage: you can argue for corrections with evidence, decide whether a raise is being properly reflected and consciously trade take‑home pay for future security via benefits. Over time, you’ll rely less on “mystery math” and more on a clear mental model of how every pay period converts your labor into a structured sequence of deductions and, finally, usable cash.