If you’ve just started working for yourself, your first “paycheck” can feel like a mystery: money comes in, a chunk disappears into taxes and expenses, and it’s not obvious where it all went. The good news: once you understand the logic behind self‑employment deductions, the numbers stop being scary and start becoming a tool you can control. Think of this as a friendly self employed tax deductions guide written for 2025 realities, not a dusty textbook from the 80‑х. We’ll unpack terms, walk through examples, and show how to see your real take‑home pay before you spend a cent.

From 19th-Century Ledgers to 2025 Apps

Historically, freelancers and small traders used paper ledgers to track income and manually guess taxes. In the early 1900s, many countries didn’t even have structured income tax; people just settled up yearly with a local official. By the 1950s, employees got pay stubs with clear lines for withholdings, while the self‑employed were still doing math by hand. Jump to 2025: digital banks, invoicing platforms, and modern tax rules make the process clearer, but also more complex. Rules change almost yearly, new deductions appear, and software automates a lot—if you know what those automated numbers actually mean and how they shape your paycheck deductions.

Key Terms: Gross Income, Net Profit, and Taxable Income

To follow your own paycheck logic, a few base terms matter. Gross income is the total you bill clients before any costs. Business expenses are ordinary and necessary costs to earn that money: software, advertising, part of your home office, travel, and so on. Net profit is what’s left after subtracting those expenses from gross income. Taxable income is net profit adjusted by specific tax rules and allowances. A simple mental diagram helps:

Income → (minus business expenses) → Net profit → (tax rules) → Taxable income → (tax rates) → Tax owed.

Once you see everything passing through these steps, each “deduction” is just one piece of that pipeline.

What Counts as a Deduction When You’re Self-Employed

Deductions are the bridge between the money you earn and the income the tax office actually cares about. For self‑employed people, typical deductible items include: software subscriptions, web hosting, professional education, marketing, a portion of rent and utilities for a home office, and part of your phone and internet. These aren’t loopholes; they recognize that you must spend money to earn money. The trick is to document them clearly—receipts, invoices, bank statements—so they survive an audit. In 2025, many banking apps auto‑tag transactions, but you still need to decide whether each cost is truly business‑related and consistently categorize it.

Seeing Deductions as a Flow Diagram

It helps to visualize your self‑employed “paycheck” as a flow rather than a single number. Imagine text blocks on one line:

Client payment → | Business expenses | → Adjusted profit → | Self‑employment tax | → | Income tax | → Money you can safely spend.

Each vertical bar marks a deduction stage. At the “Business expenses” bar, you’re reducing income through legitimate costs. At the “Self‑employment tax” bar, you’re paying Social Security and Medicare–style contributions. At the “Income tax” bar, you’re applying ordinary income tax rates. This mental diagram stops you from treating every incoming payment as spendable cash and nudges you to reserve money at each stage.

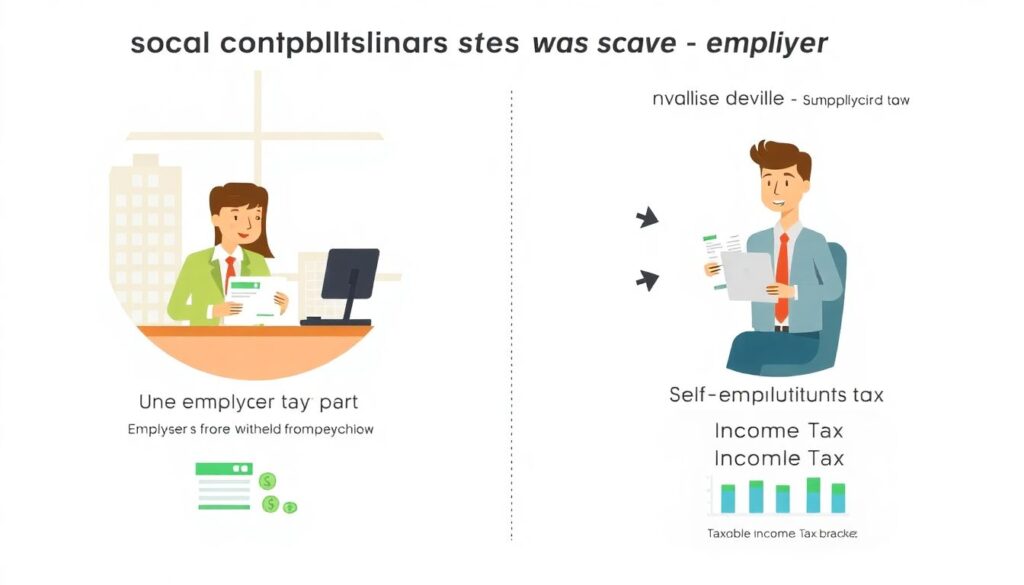

Self-Employment Tax vs Income Tax: Why Two Systems?

When you’re an employee, your employer pays part of your social contributions and withholds the rest from your paycheck. As a self‑employed person, you play both roles, so you pay both halves, grouped as “self‑employment tax.” Income tax is separate; it’s based on your taxable income and your bracket. People often confuse these and under‑save, which hurts at filing time. Think of it like this:

• Self‑employment tax → pays into social insurance systems (like Social Security/Medicare in the US).

• Income tax → funds general government operations.

Your real paycheck deductions need to cover both, plus any regional taxes, long before the deadline arrives.

How to Calculate Self Employment Tax on Paycheck Manually

You don’t need to be a CPA to understand how to calculate self employment tax on paycheck. Take one client payment period—say, a month. Step 1: total your gross income. Step 2: subtract all documented business expenses to get net profit. Step 3: multiply that net profit by the current self‑employment tax rate (in the US, roughly 15.3% on most of your profit). Step 4: estimate income tax by applying your marginal rate to taxable income after any allowances. A simplified example: $5,000 income – $1,500 expenses = $3,500 profit. Self‑employment tax ≈ $535. Income tax might be another few hundred, depending on bracket. What’s left is your practical “paycheck.”

Using Tools and Calculators Without Going Blind

In 2025, many websites offer a self employed paycheck calculator after taxes. These tools let you punch in monthly income, expected expenses, and location, then spit out estimated take‑home pay and recommended savings for taxes. They’re convenient, but only as good as the numbers you feed them. If you underestimate expenses, you’ll think your taxes are worse than they are; if you overestimate, you may not save enough. Use calculators as dashboards, not crystal balls: run a conservative scenario, then a realistic one, and compare. The gaps between them show how sensitive your cash flow is to small changes in income or costs.

Software, Spreadsheets, and What to Automate

You can manage everything with a spreadsheet, but many solo workers now pick the best accounting software for self employed taxes instead. Modern tools import bank feeds, sort expenses into categories, and estimate quarterly payments. Automation shines at repetitive tasks: matching invoices to payments, tracking mileage, flagging subscription renewals you forgot. Still, understanding the underlying math keeps you from over‑trusting the software. A quick rule: once your business passes a few regular clients or multiple income streams, software becomes cheaper than the time you’d burn fixing spreadsheet errors—and safer than mis‑classifying deductions by hand.

Legal Tactics to Keep More of Your Money

Every new freelancer sooner or later asks how to reduce self employment tax legally. The answer sits in three areas: better expense tracking, smarter business structure, and timing. First, claim all legitimate business deductions; missing even small recurring costs inflates profit and taxes. Second, in some countries, forming an LLC or similar entity and paying yourself a mix of salary and distributions can lower certain contributions—only with proper professional advice. Third, plan timing: pulling big purchases into the current year or moving work to next year can shift income across brackets. The tactic must match real business needs, not just tax goals.

Practical Habits for Predictable “Paychecks”

Understanding the theory matters, but habits keep you out of trouble. Useful routines include:

• Open a separate tax savings account and automatically move a fixed % of each payment there.

• Log expenses weekly while they’re fresh in your mind, not once a year.

• At month‑end, run a mini “self audit”: income → expenses → estimated taxes → safe spending.

Over time, this turns chaotic freelance income into something that feels like a stable paycheck. Combine a realistic rule‑of‑thumb percentage with a calculator or software, and you’ve built your personal, always‑updated self employed tax deductions guide tailored to your real numbers, not someone else’s example.