Why Smart People Still Live Paycheck to Paycheck

You can earn a solid income, be reasonably responsible, and still find yourself counting days to the next paycheck. That’s not always about discipline; often it’s about bad mental models. We copy what parents, colleagues, and “money gurus” do, and then wonder why we’re stuck. The real trap isn’t coffee or Netflix — it’s five persistent budgeting myths that quietly ruin cash flow. Once you see them as flawed algorithms instead of “truths”, you can redesign your system and finally learn how to stop living paycheck to paycheck without feeling like you’re on a permanent financial diet.

Living close to the edge is not only stressful, it’s expensive. Overdraft fees, credit card interest of 20–35% APR, and last‑minute purchases cost more than planned ones. That’s why we’ll mix conversational explanations with a bit of financial engineering: cash‑flow modeling, failure‑proof buffers, and automation. Expect some unconventional tactics too: “chaos accounts”, negative budgeting, and time‑based envelopes that work even if your income is irregular or you hate spreadsheets.

—

Myth 1: “If I Just Track Every Expense, I’ll Be Fine”

The first myth sounds logical: “I don’t need a budget, I just need to track what I spend.” Tracking is like reading a black box flight recorder after the crash. You see what happened, but too late to change the outcome. A budget is different: it is a forward‑looking allocation plan for your next dollar, not a historical diary. People install an online budget app to track expenses and savings, feel productive, then stay broke because the app is only a mirror, not a steering wheel. Data without decisions doesn’t change behavior; you need rules that act before money leaves your account.

Most people stop using trackers after a few weeks because the feedback is depressing: “You overspent. Again.” No one wants a judgmental spreadsheet. A better approach is predictive tracking: at the start of the month, you assign jobs to each dollar (housing, food, buffer, debt), and during the month the system only asks one question: “Did we follow the plan, yes or no?” This turns the budget into a simple decision engine: every purchase must “apply for a job” in your plan. If it doesn’t fit anywhere, it waits until next month.

Technical Breakdown: Forward vs. Backward Budgeting

Backward budgeting = categorize past transactions, calculate totals, feel guilty. Forward budgeting = define spending envelopes first, then route transactions into them in real time. Tools: automatic rules in banking apps, pre‑set merchant categories, and separate sub‑accounts. Implement a rule: every income event is split instantly — e.g., 55% essentials, 20% goals, 15% fun, 10% buffer. This reduces cognitive load: decisions happen once, at paycheck time, not at every coffee.

—

Myth 2: “I Don’t Earn Enough to Budget”

The second myth says: “Budgeting is for people with extra money. I’m barely covering basics.” But ignoring a budget when cash is tight is like flying through a storm with no instruments because fuel is low. The less you earn, the more critical it becomes to see every friction point. In practice, many households with modest incomes leak 5–15% monthly on unplanned micro‑spending: delivery fees, small subscriptions, interest penalties. On a $2,500 net income, 10% is $250 — that’s your emergency fund, or a debt‑kill payment, hiding in plain sight.

What helps here is not a prettier spreadsheet, but constraints that are hard to bypass. Think of “friction engineering”: make impulsive categories slower to access. For example, move your “fun money” to a separate account with a debit card that you physically leave at home during the workweek. Force a 24‑hour delay for transfers from savings to checking. Tight budgets benefit more from structural hacks than from willpower, because decision fatigue hits low‑income households first and hardest.

Technical Block: Minimum Viable Budget (MVB)

MVB is a stripped‑down personal budget planner to get out of debt and survive month to month. Only four lines: (1) Shelter & utilities, (2) Food & transport, (3) Debt & obligations, (4) Buffer + everything else. Rule: line (4) only gets money after (1)–(3) are fully funded. When income is low or unstable, you update the plan per paycheck, not per month. Each time money arrives, you re‑run the four lines in that order. This “paycheck‑centric” logic prevents you from committing next week’s grocery money to today’s impulse purchase.

—

Myth 3: “Cutting Out All Fun Is the Fastest Way to Save”

Going “no fun, no life” for months might work for ultra‑disciplined people, but for most it triggers the binge‑and‑regret cycle. Pure deprivation is brittle; one stressful week, and the whole system collapses with a big splurge. Sustainable change assumes you’re human, not a robot. Some of the best budgeting tips to save money fast actually involve spending more intentionally on joy, so you don’t compensate with random Amazon orders at midnight. The goal is not zero fun, it’s controlled fun with hard guardrails.

An unconventional solution here is the “Chaos Account”. You deliberately allocate 5–10% of income to an account whose sole purpose is guilt‑free, unpredictable spending. No tracking, no categories, just “if it’s in here, it’s legal.” Psychologically, this reduces the feeling of being trapped. Technically, it limits damage: your “chaos” is capped. People who adopt this often see total spending drop because they stop raiding rent or grocery money when stressed — they raid their controlled chaos instead, which is pre‑budgeted.

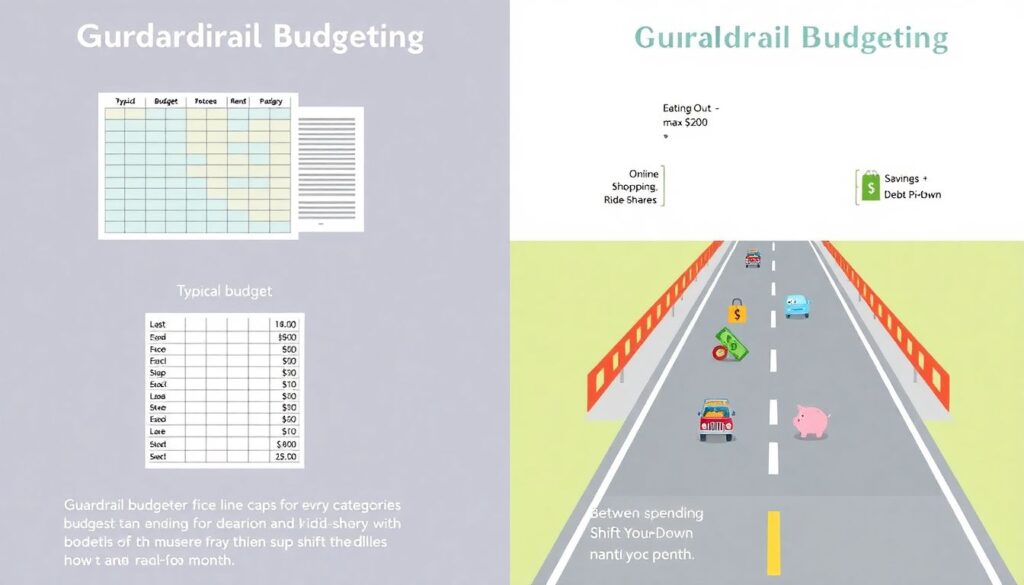

Technical Block: Guardrail‑Based Budgeting

Traditional budgets use line‑item caps for every category. Guardrail budgeting defines only maximums for risky categories (eating out, online shopping, ride‑shares) and a minimum for savings and debt pay‑down. Everything between the rails can flex month to month. Example: max $200 for restaurants, max $150 random online buys, minimum $150 emergency fund contribution. As long as you stay within rails, you’re “on budget” and don’t need to micromanage. This drastically reduces complexity while still pushing money toward long‑term goals.

—

Myth 4: “Debt First, Then I’ll Start Saving”

It sounds responsible to throw every extra dollar at debt. Mathematically, if your debt interest is 20% and savings earn 4%, killing debt looks like the dominant strategy. But living with zero cash buffer guarantees you’ll use credit again when (not if) something goes wrong. That keeps you on a revolving treadmill: pay down card, emergency hits, card spikes back up. The interest rate is only part of the equation; volatility — the size and frequency of unexpected expenses — matters just as much. Without a buffer, your financial system is unstable.

A more resilient structure is “parallel progress”: build a small emergency buffer while still killing debt aggressively. For example, until you have $1,000 in cash, route 70% of your extra money to savings and 30% to debt. Once that minimum buffer is built, reverse the ratio. This feels slower but usually gets you out of revolving credit sooner, because you stop backsliding. Think like an engineer: before you increase speed (debt payoff), you install brakes (cash reserves), otherwise every pothole throws you off the road and back into overdraft territory.

Technical Block: Volatility‑Adjusted Debt Strategy

Step 1: Estimate your “shock size” — typical surprise expenses per year (car repairs, medical, travel). Many households see $1,500–$3,000 annually. Step 2: Set your emergency fund target at 50–100% of that shock size to start; full 3–6 months of expenses can come later. Step 3: Use either the avalanche method (highest APR first) or snowball (smallest balance first) for remaining extra cash. But never let savings drop below your minimum target while you’re in payoff mode; pause debt overpayments temporarily if you dip under the buffer.

—

Myth 5: “I Just Need More Willpower”

Blaming yourself for “weak discipline” ignores how money systems actually work. Most spending decisions are automatic, habitual, and triggered by context, not by conscious choice. Supermarkets are engineered to extract more money per visit; frictionless one‑click purchases bypass reflection. Expecting sheer self‑control to win against those systems is unrealistic. The real question is: how can you design your environment so that the lazy, tired version of you still makes good choices by default?

That’s where financial automation and external support come in. Standing orders to savings, automatic bill pay, and separate goal‑based sub‑accounts act like rails on a train track. You can also use targeted financial coaching to improve money management when habits are deeply entrenched or when your situation is complex (variable income, multiple debts, business expenses). A coach or accountability partner adds a layer of external logic when your internal willpower is fried, making good behavior the path of least resistance instead of a daily battle.

Technical Block: Automation as “Artificial Willpower”

Design your cash flow so that money is moved before you see it. Example sequence on payday: (1) 10% to emergency + goals savings, (2) fixed bills funded in a bills‑only account, (3) automatic extra payment to your current target debt, (4) only the remainder lands in your everyday spending account. Align transfer dates with income dates to avoid timing issues. Review once per month, but don’t manually override day‑to‑day unless there’s a genuine emergency. In effect, you “program” your future behavior once and then run the script.

—

Unconventional Moves to Break the Paycheck Cycle

If you’ve tried traditional budgets and still feel stuck, change the game, not just the numbers. One powerful move is time‑based cash envelopes using digital accounts: create separate “Week 1, Week 2, Week 3, Week 4” sub‑accounts and preload each with its share of variable spending. You’re only allowed to use the current week’s pot. This prevents front‑loading the month (spending too much in the first 10 days) and forces natural pacing without constant math. When a week’s money is gone, you switch to zero‑cost activities until the next envelope “unlocks”.

Another non‑obvious tactic: do a 30‑day “expense migration” instead of an expense cut. For every recurring cost, ask, “Can I get the same function in a cheaper way?” Swap taxis for bike‑share passes, cable for a streaming bundle, or branded groceries for store brands. You keep the underlying benefit but downgrade the delivery mechanism. Over a year, migrations can free hundreds or thousands without feeling like punishment — that freed cash then feeds your buffer and debt plan automatically, stabilizing your system for good.

Technical Block: System Check — Are You Still at Risk?

Answer three questions: (1) If your main income stopped today, how many days could you pay essentials from cash only? (2) What is your average monthly “surprise” expense over the last 12 months? (3) Do automatic transfers move at least 10–20% of your income toward future‑you (savings + debt payoff)? If your runway is under 30 days, surprises average over $150/mo, and automation is below 10%, you’re structurally set up to live paycheck to paycheck. Adjust in this order: install automation, build the buffer, then accelerate debt payoff.

—

Putting It All Together

Escaping the paycheck hamster wheel isn’t about being perfect; it’s about changing the architecture of how money flows through your life. Kill the five myths, and you replace guilt and guesswork with a simple system: predictive budgeting instead of backward tracking, guardrails instead of deprivation, parallel saving and debt payoff, automation instead of willpower, and small buffers that absorb shocks. Combine those with a lightweight personal budget planner to get out of debt, some realistic guardrails, and perhaps a bit of outside feedback, and you finally get compounding working for you instead of against you.

If you’re wondering how to stop living paycheck to paycheck in a practical way, start with just two steps this week: automate a tiny transfer to a “chaos‑but‑capped” fun account, and set up a second automated transfer — even $20 — to a buffer fund on payday. Then, once a month, review and increase those numbers by 5–10%. It won’t feel dramatic at first, but over 6–12 months you’ll see something you might not have felt in years: space to breathe, and the freedom to make choices because you want to, not because your next paycheck says so.