Why Smart Budgeting Matters Right After Graduation

You’ve got a degree, a job offer, and maybe a half-broken coffee machine from your dorm. What you probably don’t have yet is a clear system for managing the money that’s about to start flowing into — and out of — your bank account.

Smart budgeting isn’t about living like a monk. It’s about giving every dollar a job so you can cover your needs, tackle debt, and still have a life.

In other words: money is a tool, not a mystery. Let’s unpack it.

—

Key Money Terms You Actually Need to Know

Net income vs. “my salary”

Net income is the money that actually lands in your bank account after taxes, health insurance, and other deductions. Your salary offer is *gross income* — the big, impressive number before all the subtractions.

A quick rule:

– Salary in contract = gross income

– Paycheck deposit = net income

Budgeting based on gross income is a typical rookie mistake. You think you’re earning $4,000 a month, but if only $3,100 shows up, your numbers are wrong from day one.

—

Fixed, variable and “oops” expenses

– Fixed expenses: Rent, internet, minimum loan payment — same amount every month.

– Variable expenses: Groceries, eating out, rideshares — change month to month.

– Irregular or “oops” expenses: Annual subscriptions, car repairs, gifts, medical bills.

Those “oops” costs are what blow up most first-year budgets because people pretend they don’t exist until they do.

—

Emergency fund and sinking funds

– Emergency fund: Cash set aside for real emergencies — job loss, medical issues, urgent travel for family. Not “concert tickets went on sale.”

– Sinking funds: Small amounts you save regularly for big, *expected* costs (e.g. $50/month for travel, $40/month for car maintenance).

Think of sinking funds as slow-motion budgeting for future you.

—

How to Build a First Budget That Actually Works

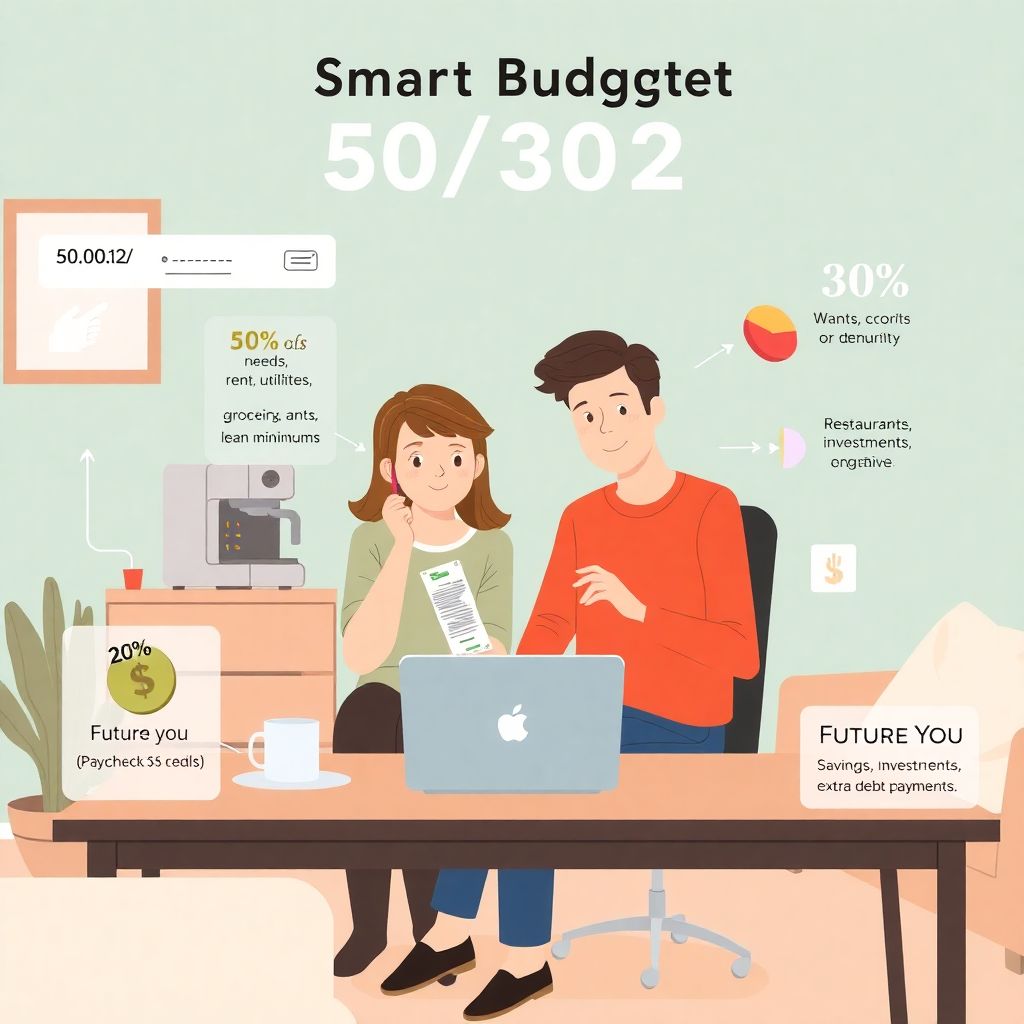

A simple visual: where your paycheck goes

Imagine your monthly net income is $3,000. A basic “budget map” might look like this:

– 50% Needs (rent, utilities, groceries, minimum loan payments) → $1,500

– 30% Wants (restaurants, streaming, hobbies, travel) → $900

– 20% Future You (savings, investments, extra debt payments) → $600

Text diagram:

> [ Paycheck $3,000 ]

> → Needs $1,500

> → Wants $900

> → Future You $600

This is based on the classic 50/30/20 rule, which is simple and great for beginners. But it’s not the only model.

—

Comparing budgeting methods (and which one suits you)

1. 50/30/20 rule

– *What it is*: Percent-based: 50% needs, 30% wants, 20% savings/debt.

– *Good for*: People who want a quick, flexible system.

– *Weakness*: Easy to drift into overspending because it’s not very detailed.

2. Zero-based budgeting

– *What it is*: Every dollar is assigned a specific job; income – expenses = 0.

– *Good for*: People with tight budgets, irregular income, or big goals (paying off loans fast).

– *Weakness*: Takes more time; can feel “strict.”

3. Envelope (or digital envelope) system

– *What it is*: You split money into “envelopes” (groceries, fun, gas) and stop spending when they’re empty.

– *Good for*: Chronic overspenders who need hard limits.

– *Weakness*: Less flexible; can feel annoying in the beginning.

For most new grads, a hybrid works well: 50/30/20 as a high-level guide, plus digital “envelopes” for problem areas like food delivery or rideshares.

—

Step-by-Step: Setting Up Your First Post-Grad Budget

1. Calculate your real take-home pay

Collect your last few pay stubs and write down:

1. Average net income (what’s actually deposited)

2. Pay frequency (every 2 weeks, twice a month, monthly)

If you’re paid every 2 weeks, remember you get 26 paychecks a year, not 24 — those two extra checks can supercharge savings or debt payoff.

—

2. List your non-negotiable expenses

Rent, minimum student loan payment, basic groceries, transportation, phone, utilities, health insurance. These are your needs, not your nice-to-haves.

If your needs alone are >60% of your net income, that’s a red flag, and you’ll need to adjust — cheaper housing, roommates, or a different transportation plan.

—

3. Put Future You in the budget from day one

This is where most recent grads slip: they promise to “save whatever’s left” at the end of the month. Spoiler: usually nothing is left.

Instead, treat saving like rent: it gets paid first. This is where concepts like how to start saving for retirement in your 20s come in. Even $50–$150 a month into a retirement account (401(k) or IRA) can matter a lot due to compound growth.

—

4. Track for 2–3 months, then adjust

Your first budget is a hypothesis. It will be wrong. That’s fine.

The useful part is tracking what actually happens — especially in categories like groceries, eating out, and online shopping. After a few months, you’ll see patterns and can re-balance your categories based on reality, not guesses.

—

Common Money Mistakes New Grads Keep Making

Mistake 1: Lifestyle creep right out of the gate

You go from living like a student to feeling rich compared to last semester. So you “reward yourself” with:

– New apartment (solo, no roommates)

– New car with a big payment

– Subscriptions you barely use

– Constant eating out because “I work hard”

Individually, each choice seems reasonable. Combined, they quietly consume your entire paycheck.

Better alternative: Upgrade slowly. Lock in reasonable rent and basic transportation for your first 1–2 years. Use the difference to build an emergency fund and attack debt.

—

Mistake 2: Ignoring student loans until the first bill hits

Many grads wait until a loan servicer email shows up to think about debt. By then, panic sets in.

A smarter path is to research student loan repayment strategies for new employees *before* payments begin:

– Can you qualify for income-driven repayment?

– Is employer loan assistance available?

– Does it make sense to refinance (only if you understand the trade-offs)?

Even an extra $25–$50 a month toward high-interest loans can cut years off repayment.

—

Mistake 3: Treating credit cards as “extra money”

A credit card is a payment tool, not a raise.

Rookie pattern:

– Use card freely → pay minimum → repeat → balance grows → interest charges explode.

If you like rewards cards, protect yourself with two rules:

1. Only buy what you could pay in cash today.

2. Set up automatic full balance payment each month.

—

Mistake 4: Zero retirement savings because “I’ll catch up later”

When you’re 22, retirement feels like science fiction. This is exactly why people postpone it and later ask how to start saving for retirement in your 20s when they’re already 29.

The uncomfortable truth: your first decade of contributions is the most powerful because of compound interest. Starting with tiny amounts is better than waiting for “perfect.”

Example:

– Person A saves $100/month from 23 to 33, then stops.

– Person B saves $100/month from 33 to 63.

Even though B contributes three times more money, A can end up with a surprisingly similar balance at retirement because A’s money had more years to grow.

—

Mistake 5: No emergency fund and no plan

Many new grads have $0 in cash savings and rely on credit cards for emergencies. That works — until it doesn’t.

Target: build 1 month of bare-bones expenses first (rent, food, basic bills), then grow toward 3–6 months over time. Start with something tiny like $20 per paycheck if that’s all you can spare, but make it automatic.

—

Tools and Apps: Automating Your Budget

Picking the right apps for your brain

There’s no universal list of the best budgeting apps for recent college graduates, because people think differently:

– If you love visuals: choose apps with charts/graphs that auto-categorize your spending.

– If you need strict control: pick apps built for zero-based budgeting or envelope-style budgeting.

– If you hate manual input: banking apps that auto-track and categorize may be enough at first.

The real “best” app is the one you actually open at least once a week.

—

A simple “money flow” diagram you can copy

Imagine this as a text-only diagram your bank accounts follow:

> [ Paycheck ]

> → 5–10% to Emergency Fund (Savings Account #1)

> → 5–10% to Long-Term Investing (401(k)/IRA)

> → Required Bills (Checking Account)

> → Fun Money (separate checking or digital envelope)

By splitting money into different destinations right away, you remove constant decision fatigue. You just spend from the right “bucket.”

—

Getting Professional Help (Without Being Rich)

When to consider outside advice

If your finances feel like a tangle of loans, new income, and confusing benefits, it can be worth exploring financial planning services for young professionals. Many firms now offer:

– One-time sessions for a flat fee

– Subscription-style advice instead of % of your investments

– Student-loan-focused planning for early-career workers

Just check that any advisor is a fiduciary (legally required to put your interests first).

—

Investing for Beginners (Yes, Even with Loans)

Separating investing from gambling

Investing is using money to buy productive assets (like broad stock index funds) that can grow over time. Gambling is betting on short-term price moves or random stocks you saw on social media.

If you’re just starting, beginner investment accounts for new graduates usually means:

– Employer 401(k) or 403(b) with a match (free money, start here)

– A Roth IRA at a low-cost brokerage

– A simple, diversified index fund or target-date fund, not day-trading

You don’t need to pick individual stocks to be an investor. In fact, most people are better off not trying.

—

Student Loans vs. Investing: Which Comes First?

There’s no single rule, but this rough order works for many graduates:

1. Get the full employer retirement match (if offered).

2. Build a small emergency fund (1 month of expenses).

3. Pay all minimums on loans and debts.

4. Attack high-interest debt (credit cards, private loans) more aggressively.

5. Increase retirement contributions and long-term investing as income grows.

This blended approach keeps you moving forward in multiple areas without ignoring debt or your future.

—

A Simple 5-Step Action Plan for Your First Year

1. Map your money

– List your net income, fixed bills, average variable spending, and all debts.

2. Choose a budget style

– Start with 50/30/20 and add stricter categories if you overspend.

3. Automate the essentials

– Auto-pay minimum debt payments, retirement contributions, and emergency savings.

4. Set one main goal per quarter

– Example: Q1 — build $500 emergency fund, Q2 — pay off one small loan, Q3 — increase 401(k) by 1–2%, Q4 — start a Roth IRA.

5. Review monthly, adjust quarterly

– Once a month, check: Did I spend what I planned? Once a quarter, ask: Can I save or invest a little more?

—

Final Thought: You Don’t Need Perfection, Just Direction

Your first year with a paycheck is less about flawless spreadsheets and more about building a few durable habits:

– Spend with intention instead of impulse.

– Save something every month, even if it feels tiny.

– Learn the basic rules of debt and investing and keep refining them.

Smart budgeting for college graduates entering the workforce isn’t about being “good with money” from day one. It’s about deciding that Future You deserves a plan — and then giving your money a job before it runs off on its own.